DECEMBER 2025 MILLS’ MUSINGS – GLORIA IN EXCELSIS DEO

For as long as I can remember, I have loved the music of the Christmas season. From Linus and Lucy Can Rock to You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch and from Frosty the Snowman to Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer, music from the animated specials of my childhood still brings a smile to my face.

Through the years, I have added an appreciation of more substantial works, including Antonio Vivaldi’s Gloria and George Friedrich Handel’s Messiah. Although they were written about 300 years ago, both are still widely performed when Christmas time is here, eloquent evidence of music’s ability to convey profound truths to human souls.

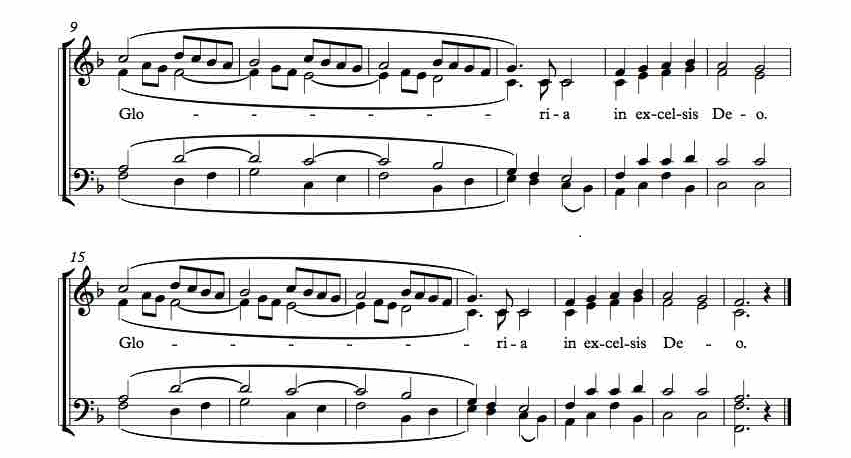

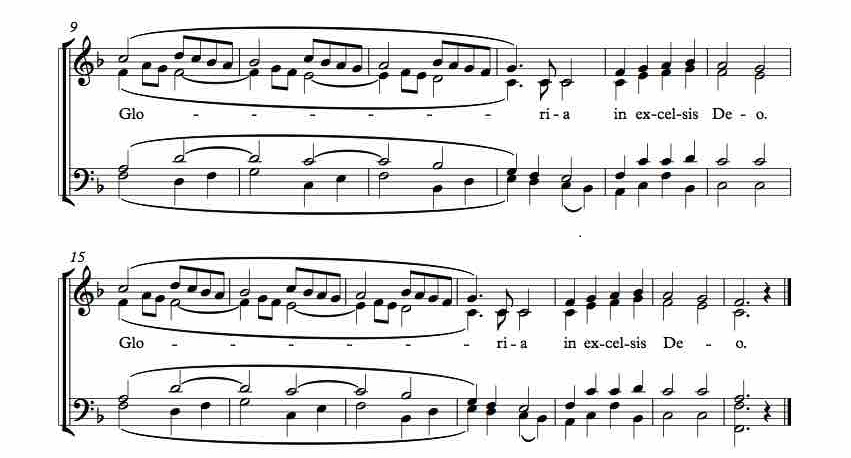

And I never tire of playing or singing Christmas carols. My favorite is Angels We Have Heard on High. The melody comes from a traditional French piece, “The Angels in Our Countryside.” “Traditional” is one way musicians say, “We have no idea who wrote this tune.”

The author of the 10 original verses is equally unknown. We do know that in 1860, these verses were translated into English by James Chadwick, a Roman Catholic bishop from England. I was surprised when I learned that it was not until 1966, when the American composer Austin Lovelace was preparing to include it in a new United Methodist hymnal, that this centuries-old carol was first given the title “Angels We Have Heard on High.”

One of my earliest musical memories is learning to sing this carol for my home church’s Christmas pageant. This annual event was the standard small church bathrobe drama, complete with shepherds and angels, wise men and a plastic baby Jesus. But with each tableau, the Junior Choir sang a verse or two from an appropriate carol. When we got to Angels We Have Heard on High, I was asked to sing the alto line for the refrain.

That was a revelation.

As the carol’s refrain began, the sopranos held their note for several beats while the altos sang shorter notes below them. Then we held a long tone while the sopranos kept changing notes above us. I was hooked. It would be years before I learned that the technical term for that musical procedure is “polyphony,” literally, “many voices.” It took me even longer to recognize that this compositional technique provides an ideal way to set the text of the carol’s refrain, which is taken from Luke 2:13-14:

And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God and saying,

“Glory to God in the highest,

and on earth peace among those with whom he is pleased!”

By definition, a multitude of angels would include many voices. Using what a former pastor called my “sanctified imagination,” I can imagine that the voices of the heavenly host ranged from low to high, each with its own distinctive timbre. And while I can’t imagine what that heavenly choir sounded like when they praised God from the sky, I’m sure that what the shepherds heard was glorious and that it glorified God in the highest.

As together we begin this new Christian year, journeying through Advent to Christmas with the music of the season ringing in our years, let me encourage you to listen a bit more carefully to the carols you’ll hear and sing. For even though we know them all by heart, if we pay a little more attention to both the words and the music, we just may find our souls refreshed in unexpected ways.

Gloria in excelsis Deo.

Read more...

November 2025 MILLS’ MUSINGS – FOR ALL THE SAINTS

On Sunday, November 2, Northminster will add an extra element to our usual order of worship – a necrology. Names of church members who have died in the past 12 months will be read aloud and followed by a single chime. It’s a simple but meaningful ritual, a practice that reminds us of two important truths about our faith. But first, a bit of history.

In the Roman Catholic Church, All Saints Day is annually celebrated on November 1st, while All Souls Day is November 2nd. In many Protestant denominations, the first Sunday in November unites these celebrations on what we call All Saints Sunday.

While there are understandable differences between Catholic and Protestant traditions, a central theme in each is celebrating the transition of believers from the Church Militant to the Church Triumphant, that is, recognizing and rejoicing with all those Christians who have finished their work on earth and now abide with God in heaven.

The first truth this celebration brings to our attention is that all Christians are saints. Both the Hebrew (OT) and Greek (NT) words translated “saint” come from a root that means “holy.” To be holy is to be set apart by God in order to serve God. Paul describes saints as “those sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints together with all those who in every place call upon the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, both their Lord and ours” (1 Cor. 1:2).

Here Paul shows us that sainthood, which is also called sanctification, (being made holy), is both a position and a process. As God’s chosen people, we have been made holy through the work of Jesus Christ on the cross. We are being made holy through our cooperation with the work of the Holy Spirit in and through us. And one day we will be made holy as we reunite with the saints who reached heaven before us.

As in our worship on All Saints Sunday we remember the saints of this congregation who now worship God in heaven, we are also reminded of a second truth – that our Christian faith is built on a firm historical foundation.

I affirm the observation made by church historian Bruce Shelley, who writes: “Many Christians today suffer from historical amnesia. The time between the apostles and their own day is one giant blank. That is hardly what God had in mind.”[1]

I suspect not many of us could cite chapter and verse of the history of Northminster Evangelical Presbyterian Church. I’m quite sure vast numbers of Presbyterians have little knowledge about the ecclesiastical developments that followed Martin Luther’s 95 Theses. Even more know less about the first 1,500 years of Christian history and theology. Such knowledge gaps impede our growth as individual Christians and as a congregation. For if we don’t know how we got to where we are, where we go next is anybody’s guess.

This All Saints Sunday, let’s rejoice with the souls we have known who now rest from their labors. And in the year between this celebration and the next, let’s spend some time looking back so that we might more clearly see the way ahead.

Read more...

MILLS’ MUSINGS – ANOTHER BIRTHDAY?

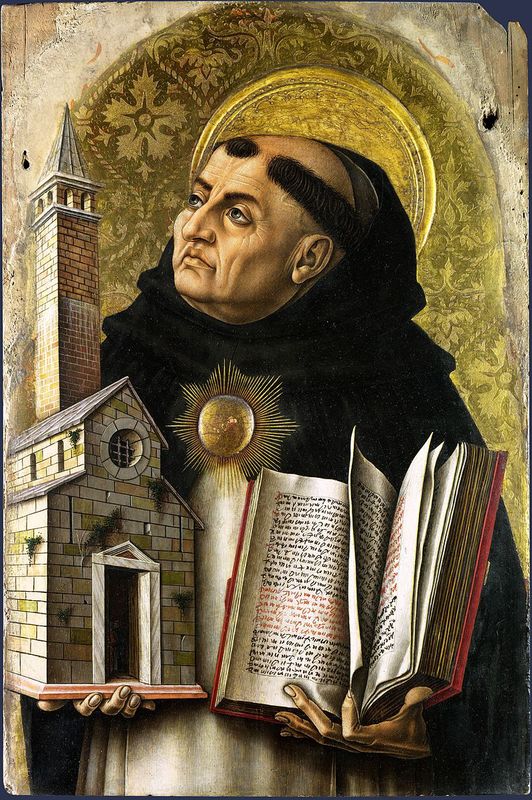

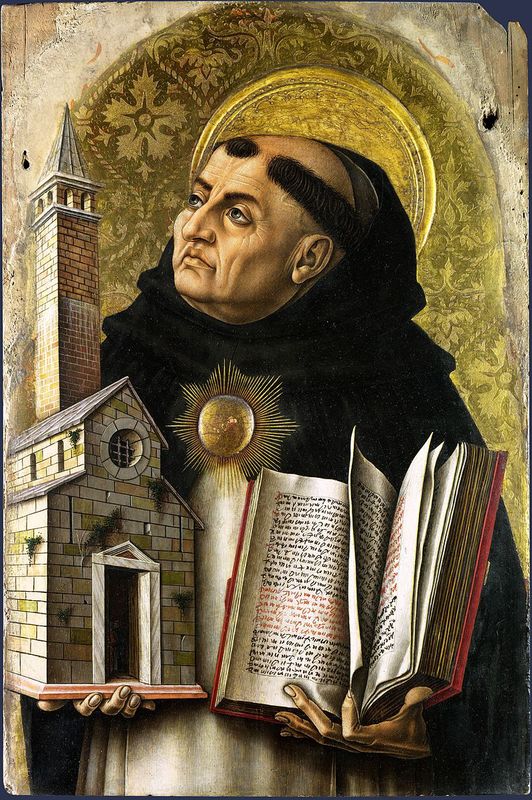

On January 28, the Roman Catholic Church annually observes the Feast of Saint Thomas Aquinas. This year, that festival celebrated the 800th anniversary of his birth.

I use that admittedly awkward phrasing because no one knows his actual birthday. From existing records, we can tell he was born either in late 1224 or early 1225. However, 13th-century Italian officials in the city of Aquino weren’t terribly fastidious about the exact dates children were born to minor noblemen. Nonetheless, the providential timing of his birth helped Aquinas become one of the most important theologians in the Christian Church and one of humanity’s most influential philosophers.

Aquinas lived and worked at a hinge point in Western culture. Europe was on the cusp of the Renaissance. Just 25 years before Aquinas’ birth, the University of Paris received its royal charter. Paris was the first university in the sense that we now use that term: an institution that teaches a variety of disciplines to both undergraduate and graduate students. And with the rise of educational institutions not run by the Roman Catholic Church, the relationship between Christian faith and human reason was undergoing its first major reevaluation in nearly a millennia. Aquinas would play a key role in that project.

As a monk in the recently formed Dominican order, Aquinas spent most of his ministry as a teacher, including at the University of Paris. A great deal of his work, in the classroom and his writings, intended to show the Church and the world that the truths of human reason, those demonstrable by the observations of the senses and the exercise of logic, are compatible with the truths of revelation, those that have been divinely disclosed by God to his human creation.

Today, Aquinas is also recognized as the culminating figure of Scholasticism. The primary aim of the late-medieval Scholastics, who were both philosophers and theologians, was to correlate Christian doctrine with human reason. The Scholastics wanted to show the reasonableness of God’s teachings. They also wanted to explain why those doctrines were important to the daily life of every Christian regardless of occupation or level of education. The Scholastics recognized Christian religion and contemporary science aren’t enemies. Rather, they saw them as complementary ways of learning about God and his world.

And yet, from the Renaissance through the Enlightenment and the Modern era, powerful forces have been trying to separate religious faith from human reason. Those forces are now waning and their centuries-old project is in peril. Most notably, the farther back in time scientists are able to see, the more their observations begin to sound like Aquinas’ articulations of his arguments for the existence and nature of God.

In his 1978 book God and the Astronomers, Robert Jastrow, founder of NASA’s Goddard Institute and an atheist, explained:

For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountains of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries.

Aquinas, I suspect, has a seat on the front row. Christians from all traditions, along with those who share his concerns if not our faith, can continue to learn from his work and celebrate his life – even if we’re not quite sure about his birthday.

Read more...

MILLS’ MUSINGS – YOU’RE GONNA NEED A BIGGER CAKE

This year the Nicene Creed celebrates its 1,700th birthday. Accommodating that many candles would require a birthday cake far larger than any I’ve ever seen. And if you’re wondering about this article’s title, you may want to rewatch Jaws, which turns 50 this year. (Anybody else feeling old?)

The Nicene Creed seems less well known to Presbyterians and other Reformed Christians than either the Apostles’ Creed or the Westminster Confession of Faith. For reasons I won’t explore here, I don’t find that surprising. But I do believe that as the Church enters its third millennium, all Christians would be well served by learning more about the background and importance of this creed as it reaches the ripe old age of 1,700.

In the year 325, the Church was still adjusting to its new status in the Roman Empire. Barely a decade earlier, the new Roman Emperor, Constantine, had converted to Christianity and issued his Edict of Toleration, which legalized the faith in the empire. The Edict would prove a mixed blessing. Official persecution of Christians ended and Church membership grew rapidly. Unfortunately, with growth came controversy.

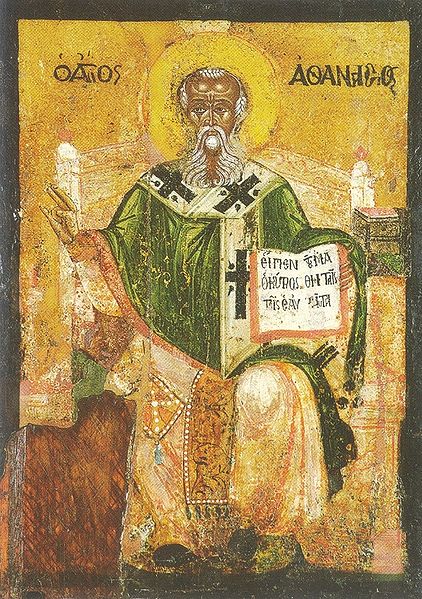

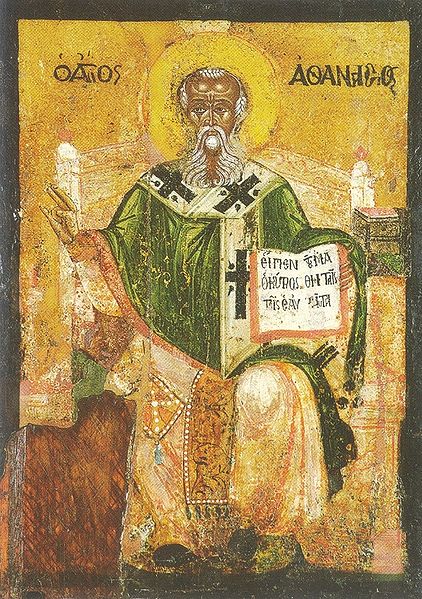

As early as 318, a pastor named Arius began teaching that Jesus was not fully God; that Jesus was not eternal, but instead was the first creature made by God. This new doctrine contradicted Scripture and three centuries of Church teaching. To resolve the conflict in the Church, and not coincidentally to help keep peace in his empire, Constantine called for a council of church leaders to meet in city of Nicaea in 325.

There, Arius was given the opportunity to explain his beliefs to the bishops. He and his supporters were sure his views would prevail. However, his novel teaching, summarized by the slogan “There was when the Son was not,” was opposed by one of the most able and influential theologians of the Early Church, Athanasius. Athanasius insisted that if Jesus wasn’t fully God, he couldn’t fully accomplish human salvation. “That which has not been assumed has not been healed,” was his succinct response.

Rejecting as heretical Arius’ insistence that Jesus was not God, the Council of Nicaea produced the Nicene Creed, which declared that Jesus is “of one substance” (homoousia) with the Father. Homoousia combines homo, meaning same, with ousia, meaning substance, or essence. The Greek word isn’t found in the Bible, which troubled some members of the council. But as the Church worked to articulate the Bible’s unchanging revelation in the language of its day, homoousia seemed the best word to express the eternal relationship between God the Father and God the Son.

The importance of the Nicene Creed in Christian history is summarized by the late Presbyterian theologian John Leith who writes, “The first Christian doctrine that the church settled in an ecumenical council and that has subsequently received approval in the life of the church through the centuries had to do with the deity of Jesus Christ. The church made clear at Nicaea what it was convinced had always been the faith of Christian people. In Jesus Christ human beings are confronted by God.”

For nearly two millennia, the Nicene Creed has remained the most widely quoted creed in Christendom. It’s accepted by Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Anglicans, and most Protestant denominations. Each time we recite this historic affirmation of our faith, we remind ourselves of a fundamental Christian truth: God’s nature is Triune. We also remind ourselves of our unbreakable connection to Christians around the world and throughout time.

So, on the 1,700th birthday of the Nicene Creed, a cake may be in order. Especially if we fudge the candles.

Read more...

MILLS’ MUSINGS – THE HUMAN CAPACITY FOR BEAUTY

A man should hear a little music, read a little poetry, and see a fine picture every day of his life, in order that worldly cares may not obliterate the sense of the beautiful which God has implanted in the human soul. – Johnann Wolfgang von Goethe

I turned on the TV just as the cardinals were entering the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel. Once the door closed behind them, they would begin the conclave that would elect Pope Leo XIV. As the cardinals came into the chapel, each one paused, put his right hand on the Book of the Gospels, and sealed his oath not to reveal what happened in the conclave.

As they did, they stood facing The Last Judgment, an enormous (45 × 39 feet) fresco by the Renaissance artist Michelangelo. Inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy, the painting was unveiled on October 31, 1541, exactly 24 years after Martin Luther posted the 95 theses that launched the Protestant Reformation.

Five years before Luther’s bold declaration, Michelangelo completed what is widely understood to be his greatest work, the Sistine Chapel Ceiling. Although he had been commissioned to paint the 12 apostles, Michelangelo instead filled the chapel’s ceiling with scenes from the Old Testament.

These frescoes were the largest, but by no means the only, works of art surrounding the cardinals as they prepared themselves for one of their highest duties. As their solemn, unhurried procession unfolded, the news anchor was joined by a gentleman who had spent several years working at the Vatican. She asked how he reacted the first time he set foot in the Sistine Chapel. After a brief pause, he answered:

“I was stunned by the human capacity for beauty.”

This was not the first time I had heard a commentator talk about the beauty of the setting and the moment. But it may have been the first time I heard anyone use the words, “the human capacity for beauty.” That fine-tuned phrase was a welcome reminder that the God who made us in His image created us not only with the innate ability to recognize and enjoy His infinitely varied gifts of beauty, but also with the indelible awareness that shining through the beauty we can access with our physical senses is the One whose very nature is the basis of all beauty, the Triune God.

Sadly, in recent centuries, the notion that God is Beauty (as well as Goodness and Truth) has been scorned in our culture and, for the most part, ignored in our churches. The consequences have been severe. Once we uncritically accept the unbiblical assertion that beauty is in the eye of the beholder, it is a very short step to saying the same about goodness and truth.

Offering a valuable corrective, John Hugo notes, “In both the tabernacle and the Solomonic temple, artistic design, metal craft, sculpture, architecture, and textile arts were employed with God’s blessing and special inspiration (Exod. 31:3-11; Chron. 28:11-21). These examples show that God has uses for the artistic skills of people and that art works are fit vehicles for serving Him.” (Emphasis added.)

I believe the cardinals in the Sistine Chapel were well served by the works of Michelangelo, Botticelli, and others. I also believe that Protestants are well served by beautiful things like stained glass windows and paraments, banners and flowers, hymn texts, piano, and organ (pace, Calvin). For I believe that as we intentionally employ our God-given gift of appreciating beauty, not only we will be drawn closer to God, but we will open those doors so that others may follow that path as well.

Read more...