DECEMBER 2025 MILLS’ MUSINGS – GLORIA IN EXCELSIS DEO

For as long as I can remember, I have loved the music of the Christmas season. From Linus and Lucy Can Rock to You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch and from Frosty the Snowman to Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer, music from the animated specials of my childhood still brings a smile to my face.

Through the years, I have added an appreciation of more substantial works, including Antonio Vivaldi’s Gloria and George Friedrich Handel’s Messiah. Although they were written about 300 years ago, both are still widely performed when Christmas time is here, eloquent evidence of music’s ability to convey profound truths to human souls.

And I never tire of playing or singing Christmas carols. My favorite is Angels We Have Heard on High. The melody comes from a traditional French piece, “The Angels in Our Countryside.” “Traditional” is one way musicians say, “We have no idea who wrote this tune.”

The author of the 10 original verses is equally unknown. We do know that in 1860, these verses were translated into English by James Chadwick, a Roman Catholic bishop from England. I was surprised when I learned that it was not until 1966, when the American composer Austin Lovelace was preparing to include it in a new United Methodist hymnal, that this centuries-old carol was first given the title “Angels We Have Heard on High.”

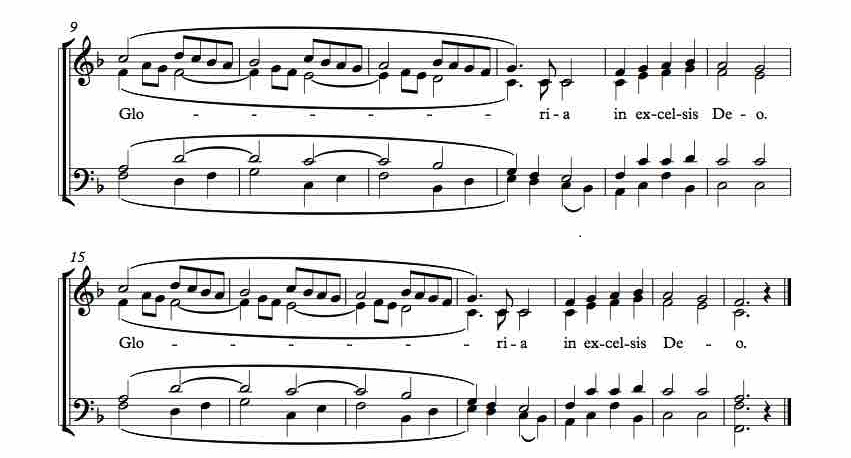

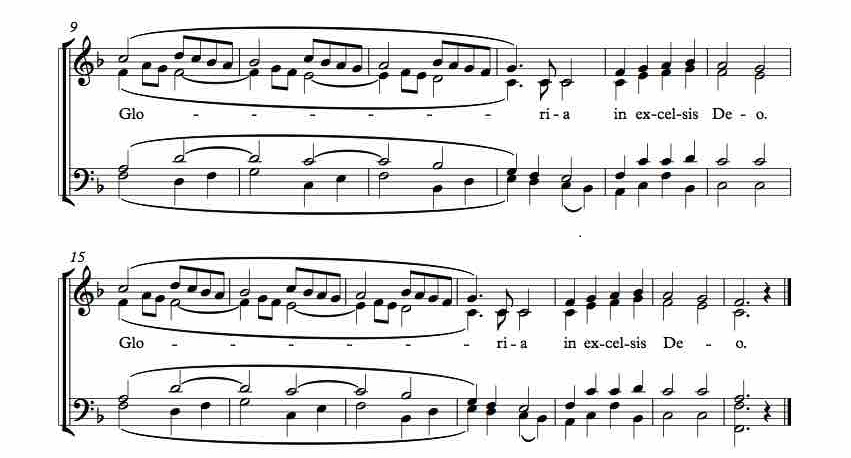

One of my earliest musical memories is learning to sing this carol for my home church’s Christmas pageant. This annual event was the standard small church bathrobe drama, complete with shepherds and angels, wise men and a plastic baby Jesus. But with each tableau, the Junior Choir sang a verse or two from an appropriate carol. When we got to Angels We Have Heard on High, I was asked to sing the alto line for the refrain.

That was a revelation.

As the carol’s refrain began, the sopranos held their note for several beats while the altos sang shorter notes below them. Then we held a long tone while the sopranos kept changing notes above us. I was hooked. It would be years before I learned that the technical term for that musical procedure is “polyphony,” literally, “many voices.” It took me even longer to recognize that this compositional technique provides an ideal way to set the text of the carol’s refrain, which is taken from Luke 2:13-14:

And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God and saying,

“Glory to God in the highest,

and on earth peace among those with whom he is pleased!”

By definition, a multitude of angels would include many voices. Using what a former pastor called my “sanctified imagination,” I can imagine that the voices of the heavenly host ranged from low to high, each with its own distinctive timbre. And while I can’t imagine what that heavenly choir sounded like when they praised God from the sky, I’m sure that what the shepherds heard was glorious and that it glorified God in the highest.

As together we begin this new Christian year, journeying through Advent to Christmas with the music of the season ringing in our years, let me encourage you to listen a bit more carefully to the carols you’ll hear and sing. For even though we know them all by heart, if we pay a little more attention to both the words and the music, we just may find our souls refreshed in unexpected ways.

Gloria in excelsis Deo.

Read more...

November 2025 MILLS’ MUSINGS – FOR ALL THE SAINTS

On Sunday, November 2, Northminster will add an extra element to our usual order of worship – a necrology. Names of church members who have died in the past 12 months will be read aloud and followed by a single chime. It’s a simple but meaningful ritual, a practice that reminds us of two important truths about our faith. But first, a bit of history.

In the Roman Catholic Church, All Saints Day is annually celebrated on November 1st, while All Souls Day is November 2nd. In many Protestant denominations, the first Sunday in November unites these celebrations on what we call All Saints Sunday.

While there are understandable differences between Catholic and Protestant traditions, a central theme in each is celebrating the transition of believers from the Church Militant to the Church Triumphant, that is, recognizing and rejoicing with all those Christians who have finished their work on earth and now abide with God in heaven.

The first truth this celebration brings to our attention is that all Christians are saints. Both the Hebrew (OT) and Greek (NT) words translated “saint” come from a root that means “holy.” To be holy is to be set apart by God in order to serve God. Paul describes saints as “those sanctified in Christ Jesus, called to be saints together with all those who in every place call upon the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, both their Lord and ours” (1 Cor. 1:2).

Here Paul shows us that sainthood, which is also called sanctification, (being made holy), is both a position and a process. As God’s chosen people, we have been made holy through the work of Jesus Christ on the cross. We are being made holy through our cooperation with the work of the Holy Spirit in and through us. And one day we will be made holy as we reunite with the saints who reached heaven before us.

As in our worship on All Saints Sunday we remember the saints of this congregation who now worship God in heaven, we are also reminded of a second truth – that our Christian faith is built on a firm historical foundation.

I affirm the observation made by church historian Bruce Shelley, who writes: “Many Christians today suffer from historical amnesia. The time between the apostles and their own day is one giant blank. That is hardly what God had in mind.”[1]

I suspect not many of us could cite chapter and verse of the history of Northminster Evangelical Presbyterian Church. I’m quite sure vast numbers of Presbyterians have little knowledge about the ecclesiastical developments that followed Martin Luther’s 95 Theses. Even more know less about the first 1,500 years of Christian history and theology. Such knowledge gaps impede our growth as individual Christians and as a congregation. For if we don’t know how we got to where we are, where we go next is anybody’s guess.

This All Saints Sunday, let’s rejoice with the souls we have known who now rest from their labors. And in the year between this celebration and the next, let’s spend some time looking back so that we might more clearly see the way ahead.

Read more...

MILLS’ MUSINGS – ANOTHER BIRTHDAY?

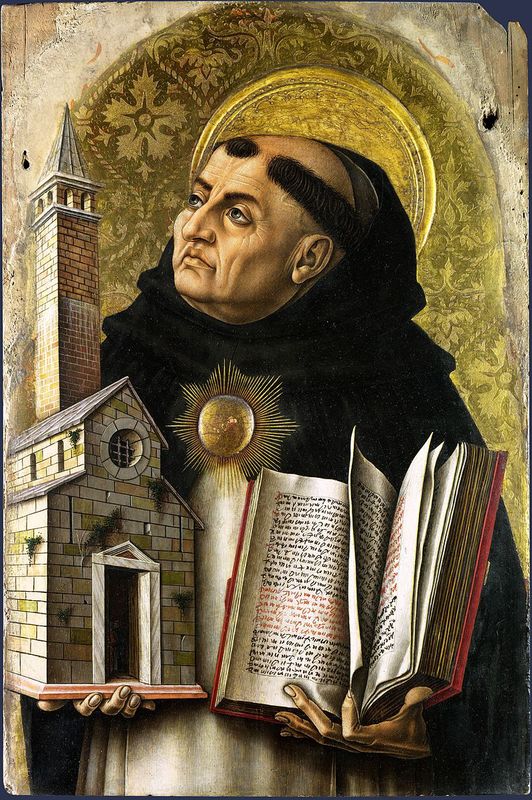

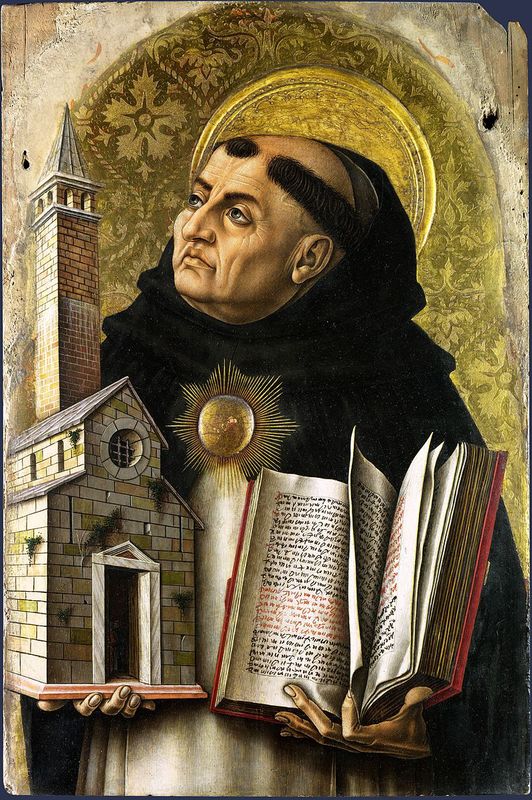

On January 28, the Roman Catholic Church annually observes the Feast of Saint Thomas Aquinas. This year, that festival celebrated the 800th anniversary of his birth.

I use that admittedly awkward phrasing because no one knows his actual birthday. From existing records, we can tell he was born either in late 1224 or early 1225. However, 13th-century Italian officials in the city of Aquino weren’t terribly fastidious about the exact dates children were born to minor noblemen. Nonetheless, the providential timing of his birth helped Aquinas become one of the most important theologians in the Christian Church and one of humanity’s most influential philosophers.

Aquinas lived and worked at a hinge point in Western culture. Europe was on the cusp of the Renaissance. Just 25 years before Aquinas’ birth, the University of Paris received its royal charter. Paris was the first university in the sense that we now use that term: an institution that teaches a variety of disciplines to both undergraduate and graduate students. And with the rise of educational institutions not run by the Roman Catholic Church, the relationship between Christian faith and human reason was undergoing its first major reevaluation in nearly a millennia. Aquinas would play a key role in that project.

As a monk in the recently formed Dominican order, Aquinas spent most of his ministry as a teacher, including at the University of Paris. A great deal of his work, in the classroom and his writings, intended to show the Church and the world that the truths of human reason, those demonstrable by the observations of the senses and the exercise of logic, are compatible with the truths of revelation, those that have been divinely disclosed by God to his human creation.

Today, Aquinas is also recognized as the culminating figure of Scholasticism. The primary aim of the late-medieval Scholastics, who were both philosophers and theologians, was to correlate Christian doctrine with human reason. The Scholastics wanted to show the reasonableness of God’s teachings. They also wanted to explain why those doctrines were important to the daily life of every Christian regardless of occupation or level of education. The Scholastics recognized Christian religion and contemporary science aren’t enemies. Rather, they saw them as complementary ways of learning about God and his world.

And yet, from the Renaissance through the Enlightenment and the Modern era, powerful forces have been trying to separate religious faith from human reason. Those forces are now waning and their centuries-old project is in peril. Most notably, the farther back in time scientists are able to see, the more their observations begin to sound like Aquinas’ articulations of his arguments for the existence and nature of God.

In his 1978 book God and the Astronomers, Robert Jastrow, founder of NASA’s Goddard Institute and an atheist, explained:

For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountains of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries.

Aquinas, I suspect, has a seat on the front row. Christians from all traditions, along with those who share his concerns if not our faith, can continue to learn from his work and celebrate his life – even if we’re not quite sure about his birthday.

Read more...