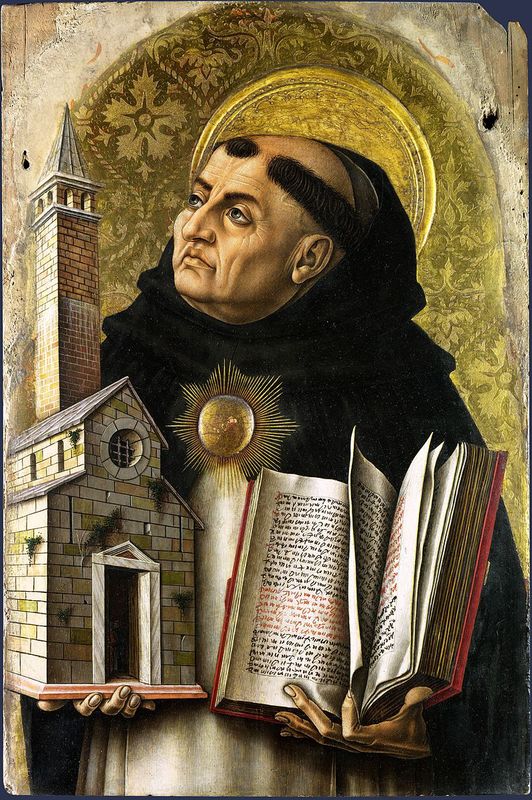

On January 28, the Roman Catholic Church annually observes the Feast of Saint Thomas Aquinas. This year, that festival celebrated the 800th anniversary of his birth.

I use that admittedly awkward phrasing because no one knows his actual birthday. From existing records, we can tell he was born either in late 1224 or early 1225. However, 13th-century Italian officials in the city of Aquino weren’t terribly fastidious about the exact dates children were born to minor noblemen. Nonetheless, the providential timing of his birth helped Aquinas become one of the most important theologians in the Christian Church and one of humanity’s most influential philosophers.

Aquinas lived and worked at a hinge point in Western culture. Europe was on the cusp of the Renaissance. Just 25 years before Aquinas’ birth, the University of Paris received its royal charter. Paris was the first university in the sense that we now use that term: an institution that teaches a variety of disciplines to both undergraduate and graduate students. And with the rise of educational institutions not run by the Roman Catholic Church, the relationship between Christian faith and human reason was undergoing its first major reevaluation in nearly a millennia. Aquinas would play a key role in that project.

As a monk in the recently formed Dominican order, Aquinas spent most of his ministry as a teacher, including at the University of Paris. A great deal of his work, in the classroom and his writings, intended to show the Church and the world that the truths of human reason, those demonstrable by the observations of the senses and the exercise of logic, are compatible with the truths of revelation, those that have been divinely disclosed by God to his human creation.

Today, Aquinas is also recognized as the culminating figure of Scholasticism. The primary aim of the late-medieval Scholastics, who were both philosophers and theologians, was to correlate Christian doctrine with human reason. The Scholastics wanted to show the reasonableness of God’s teachings. They also wanted to explain why those doctrines were important to the daily life of every Christian regardless of occupation or level of education. The Scholastics recognized Christian religion and contemporary science aren’t enemies. Rather, they saw them as complementary ways of learning about God and his world.

And yet, from the Renaissance through the Enlightenment and the Modern era, powerful forces have been trying to separate religious faith from human reason. Those forces are now waning and their centuries-old project is in peril. Most notably, the farther back in time scientists are able to see, the more their observations begin to sound like Aquinas’ articulations of his arguments for the existence and nature of God.

In his 1978 book God and the Astronomers, Robert Jastrow, founder of NASA’s Goddard Institute and an atheist, explained:

For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountains of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries.

Aquinas, I suspect, has a seat on the front row. Christians from all traditions, along with those who share his concerns if not our faith, can continue to learn from his work and celebrate his life – even if we’re not quite sure about his birthday.